Religious cults were a big deal in the 1970s. I became intrigued by how these personality-led movements attracted such loyal followers.

Some deprogramming efforts —initiated by concerned family or friends — were controversial. Not all were successful.

The loyalty created by a cult leader is deeply emotional, strong and beyond rational considerations.

This was my observation when watching several fellow college students engage in a cult-like movement that claimed to offer deeper spirituality in exchange for a measure of control over their lives.

The horrific Jonestown mass murder-suicide took place in November 1978 — during my first semester of seminary. It was a helpful place to explore cult attraction more carefully at an academic level.

My foremost observation was that cult followers end up in places they would have sworn beforehand that they’d never go. It is one step at a time in full allegiance to a leader that has them affirming and doing things previously considered well out of personal and ethical bounds.

My continuing interest over the years led to various research efforts and writings — one of which is included in the Jonestown Project used for ongoing research purposes.

During my first career, campus ministry, starting in the early 1980s, I watched Christian college students being drawn by authoritarian leaders eager to control their time, values and decision making.

In each case the leader demanded full loyalty, kept much in secret, and condemned any critique or opposition as the work of an enemy or apostate.

In response, I led a retreat on Christian decision making — focused on how the image of God concept implies personal responsibility as a divine gift not to be turned over to others. Word spread and I was soon leading similar retreats and seminars for other schools.

Wanting to dig more deeply and test my conclusions in an academic setting, I enrolled in a doctoral program at Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Ga. Two professors — one an ethicist and the other a specialist in faith development— guided my work.

A particular focus was on the damaging and often secretive teachings of Bill Gothard — whose basic seminar I attended and critiqued as part of my dissertation. Mostly, I was stunned by how participants blindly accepted his most ridiculous, misogynistic and unorthodox teachings.

Gothard’s misdeeds in the name of God were much later recounted in the documentary, Shiny, Happy People, and in the 2020 best-selling book, Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, by historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez.

So, with more than a casual understanding of cults, I was quite hesitant a few years ago when the label was first applied to those drawn into the MAGA movement. I decided to watch closely to see what ingredients go into the mix.

With some variations, cults are largely marked by authoritarian leadership without accountability, a sense of solely holding truths(even if verifiable disproven), embracing unfounded conspiracies and giving uncritical allegiance to the leader and movement.

Fear plays a major role — exploiting insecurities and drawing in those looking for comforting answers, convenient scapegoats and a sense of belonging.

The strongest identifying mark, however, is a leader with specific characteristics.

In a 2012 article in Psychology Today, former FBI Counterintelligence Agent Joe Navarro addressed the question, “What makes a pathological cult leader?”

Here are some descriptors he noted — from 12 years ago:

A cult leader “has a grandiose idea of who he is and what he can achieve” — and “is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power or brilliance.”

He “demands blind, unquestioned obedience” and “requires excessive admiration from followers and outsiders.”

The leader “has a sense of entitlement—expecting to be treated as special at all times.”

He “exploits others by asking for their money…,” and “is arrogant and haughty in his behavior or attitude.”

The cult leader has “an exaggerated sense of power (entitlement) that allows him to bend rules and break laws.”

He “takes sexual advantage of members of his sect or cult.”

Among other characteristics, a cult leader “is hypersensitive to how he is seen or perceived by others.” He is“ frequently boastful of accomplishments” and “need to be the center of attention.”

Usually men, a cult leader“ ensures being noticed by arriving late,” and his “communication is usually one-way, in the form of dictates.”

Navarro discovered from his many years of research and counterintelligence that a cult leader, when criticized, “tends to lash out not just with anger but with rage. ”And anyone who questions him is deemed an “enemy.”

The cult leader is “superficially charming” — while treating others “with contempt and arrogance.”

This was written a dozen years ago, mind you. Navarro was describing a distilled profile — from studying many cult leaders — of what goes into the personality mix.

“[W]hat stands out about these individuals is that they were or are all pathologically narcissistic,” Navarro concluded. “They all have or had an over-abundant belief that they were special, that they and they alone had the answers to problems, and that they had to be revered.”

“They demanded perfect loyalty from followers, they overvalued themselves and devalued those around them,” he concluded.“They were intolerant of criticism and, above all, did not like being questioned or challenged.”

Navarro noted that which brings surprise to many of us now: “Yet despite these less-than-charming traits, they [cult leaders] had no trouble attracting those who were willing to overlook these features.”

Then he warned: “If you know of a cult leader who has many of these traits there is a high probability that they are hurting those around them emotionally, psychologically, physically, spiritually, or financially.”

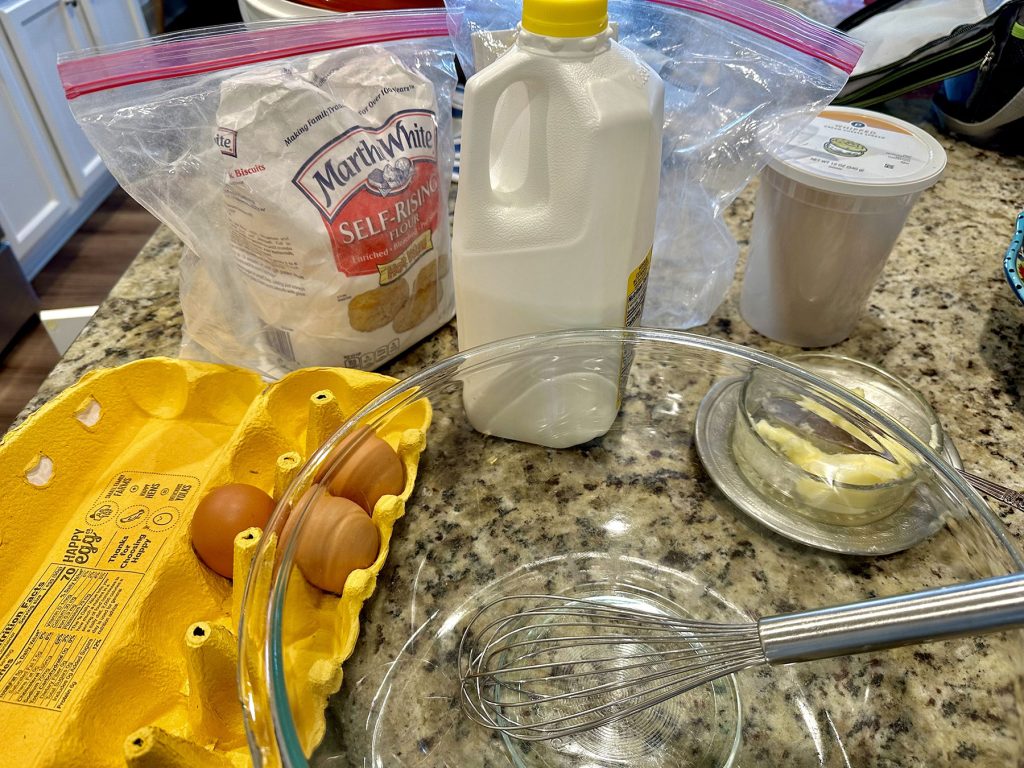

It doesn’t take a lot of expertise to know that what goes into the mix determines what comes out.

Like reading labels on food products, one can discover cult behavior by paying attention to the ingredients that are mixed in.

John D. Pierce is director of the Jesus Worldview Initiative (jesusworldview.org), part of Belmont University’s Rev. Charlie Curb Center for Faith Leadership.